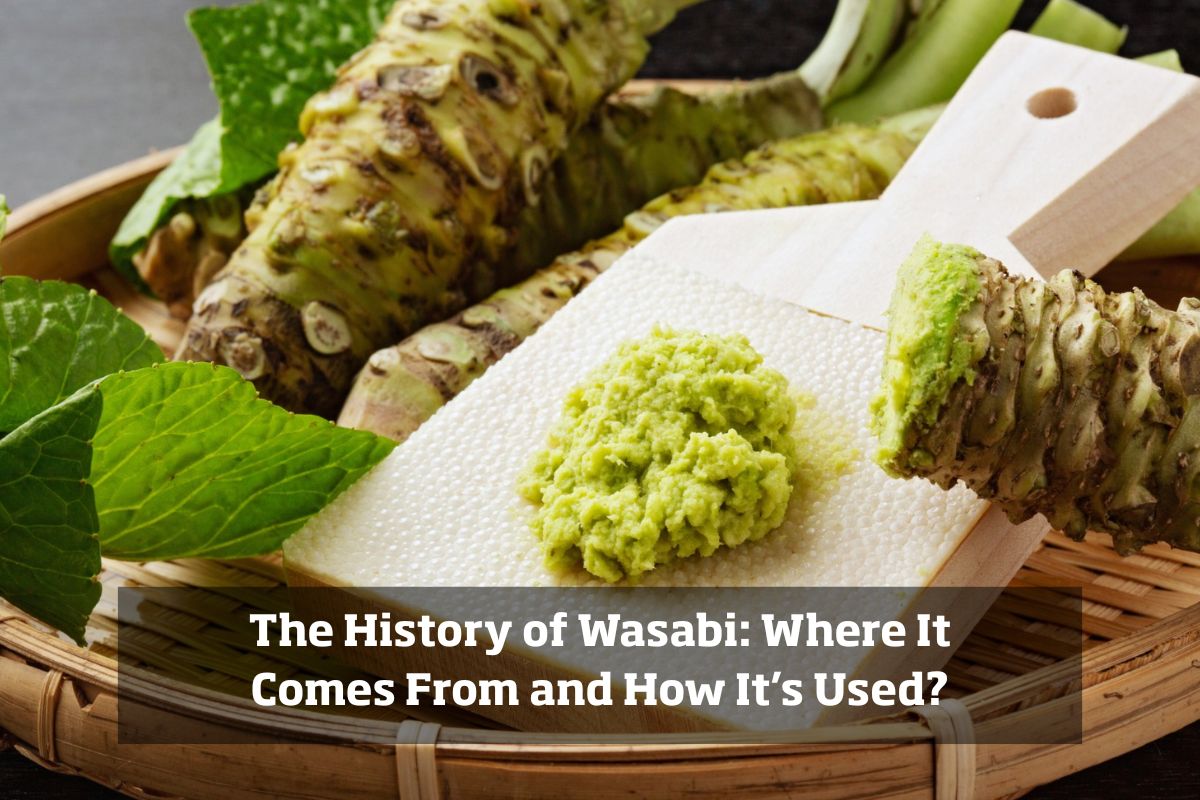

Wasabi, often known for its fiery kick in sushi dishes, is a revered condiment that has carved a unique niche in Japanese cuisine and is now appreciated worldwide. This spicy green paste comes from the root of the Wasabia japonica plant, a member of the Brassicaceae family (related to horseradish, cabbage, and mustard). Its history and uses are as fascinating as its flavour, and understanding the journey of wasabi can deepen appreciation for this green gem in our food.

Origins and Early Use of Wasabi

Wasabi has deep roots in Japan, where it has been cultivated for centuries. Its use dates back to ancient Japan, with records suggesting that wasabi was consumed as early as the 10th century during the Heian period (794–1185 AD). Initially, wild wasabi was likely used by native Japanese, who would have stumbled upon its unique taste and medicinal qualities. The plant primarily grows in mountainous regions, especially along streams, as it requires fresh, running water and a particular climate to thrive. Some of the best wasabi comes from areas like Shizuoka, Nagano, and Iwate, where the conditions are ideal for the plant’s delicate growth requirements.

The word “wasabi” is derived from two Japanese characters: 山 (yama), meaning “mountain,” and 葉 (ha), meaning “leaf.” This reflects its natural habitat, often found growing on riverbeds in mountainous areas. Over time, wasabi became more than just a wild plant; it was cultivated and cherished by Japanese nobility, who were captivated by its flavour and medicinal properties.

The Medicinal Roots of Wasabi

Historically, wasabi wasn’t just a culinary delight—it was also used for its health benefits. Traditional Japanese medicine recognized wasabi’s antibacterial and antimicrobial properties. The spice was believed to ward off illnesses and was used to treat digestive issues, respiratory problems, and even infections. The antibacterial qualities of wasabi are particularly relevant when paired with raw fish, as it can help reduce the risk of foodborne illness. This historical practice of combining wasabi with raw fish, like sashimi and sushi, was as much a health consideration as it was a culinary choice.

The Role of Wasabi in Japanese Cuisine

Today, wasabi is synonymous with Japanese cuisine, especially sushi and sashimi. Its unique, clean heat is distinct from the spiciness of chilli peppers, which burn on the tongue; wasabi instead provides a sharp, fleeting heat that clears the sinuses. This makes it a perfect pairing for fresh, delicate flavours in Japanese cuisine. When eaten with sushi, wasabi enhances the flavours of the fish, rice, and seaweed without overpowering them.

Wasabi is also commonly used in other dishes, such as soba noodles, tempura, and sauces. One unique preparation includes “wasabi zuke,” a dish that combines the pickled wasabi stems and leaves with sake lees (the residue from sake production) to create a pungent side dish with a slightly sweet flavor. This dish demonstrates how every part of the wasabi plant can be used, making it a zero-waste plant in Japanese culinary traditions.

Real Wasabi vs. Imitation Wasabi

A surprising fact about wasabi is that what most people consume outside of Japan is not true wasabi. Real wasabi, also known as hon wasabi, is difficult to grow and has a short shelf life, making it costly. This has led to the widespread use of imitation wasabi, which is typically a mixture of horseradish, mustard, starch, and green food colouring. While imitation wasabi can still provide a similar heat profile, it lacks the complex, fresh flavour of real wasabi.

Only a few places outside of Japan have succeeded in cultivating authentic wasabi, with small farms in North America and Europe attempting to replicate the specific conditions needed for its growth. Real wasabi is grated from the stem using a fine grater, often made of sharkskin, as traditional Japanese chefs believe this grating method enhances its unique flavour and texture.

Wasabi Beyond Japan: A Global Phenomenon

Over the past few decades, wasabi has gained international popularity, largely due to the globalisation of Japanese cuisine. Sushi restaurants have spread across the globe, introducing wasabi to people who may have never encountered it before. Today, wasabi is not only a staple in Japanese restaurants worldwide but is also used creatively in fusion dishes and Western cuisine. Wasabi-flavoured snacks, such as peas, chips, and sauces, are increasingly popular and provide a unique taste experience that blends heat with a hint of freshness.

Moreover, chefs and food enthusiasts worldwide have started experimenting with wasabi in novel ways. It has found its way into salads, dressings, and even desserts. Some bold chefs have paired wasabi with chocolate or ice cream, balancing the heat of the wasabi with the sweetness of the dessert for a surprising flavour combination.

Challenges in Growing Wasabi

Real wasabi remains a challenging crop to cultivate. It requires specific environmental conditions: cool temperatures, high humidity, and fresh, flowing water. The plant is prone to disease, making it labour-intensive and costly to grow. These conditions contribute to wasabi’s status as one of the world’s most expensive crops.

The rarity of real wasabi and the difficulty in its cultivation only add to its allure. Its scarcity and high cost mean that wasabi connoisseurs are willing to pay a premium for authentic wasabi, appreciating its nuanced flavour that cannot be replicated by substitutes.

Conclusion: Wasabi’s Enduring Legacy

From its humble origins in Japan’s mountain streams to its global popularity, wasabi has become an iconic element of Japanese cuisine and culture. Its rich history and unique flavour make it a favourite among those who appreciate the artistry of food. Whether enjoyed with sushi or used as a bold flavour in unexpected dishes, wasabi remains a testament to the power of tradition and the endless possibilities of culinary innovation.